Pelvic Floor Rehabilitation

Pelvic floor dysfunction affects nearly 50% of women after childbirth, so I’m sooo glad we finally got to talk about it!

Even if it’s been a while since you’ve given birth, it’s never too late to circle back and address your pelvic floor problems. Sadly, most traditional doctors don’t ask about this and don’t proactively treat these problems with their patients like they do in Europe and Canada, for example.

Pelvic floor problems include the following:

- urinary incontinence (most common!)

- fecal incontinence (usually following a level 3 or 4 tear)

- pelvic organ prolapse

- chronic pain

- diastasis recti (abdominal separation)

- pain during sex (or sex is different — and not in a good way)

- sensory and emptying abnormalities of the bladder or urinary tract

We finally interviewed my favorite pelvic therapist on the topic of rehabilitation of the common postpartum pelvic floor problems. If you can’t watch the video, the transcript is below. Enjoy!

Participants:

- Meg Collins, Editor of Lucie’s List

- Allison Romero, Pelvic Rehabilitation Therapist at Reclaim Pelvic Therapy

RECORDING COMMENCES:

Meg Collins:

Allison is my pelvic floor therapist, and today we are discussing a topic that I have been wanting to discuss for five years. Literally. It’s been on my agenda for a good four to five years. Shame on me.

I wanted to open up in the general discussion about what happens to the pelvis during pregnancy and postpartum. Then, we’ll talk about all the things that can go wrong.

Allison Romero:

Great! So, in pregnancy, the pelvis changes. Around the second trimester, we start getting some relaxin going through our body, which is a hormone that starts to loosen the ligaments.

The pelvis isn’t moving that much in the second trimester, but it’s starting to prepare to be moved. In the third trimester, starting at about 28 weeks, the ligaments start to really relax in the abdomen and in the pelvis as well. The pelvis actually starts to move. That’s where we see pregnant people start to waddle a little bit. It’s harder to get up, down, obviously because of our size and weight, but also because you don’t have the same support.

Meg Collins:

Is round ligament pain related to that?

Allison Romero:

No, it’s different. Round ligament pain is from the ligament that attaches the uterus to the abdominal wall. So, we usually find that in the second trimester, when your belly is growing. That’s a new stretching movement that you haven’t felt before.

Relaxin is more about the ligaments that are attached in our SI joint, the sacroiliac joint, and just around the pubic synthesis and the pelvic side. The pelvis starts opening right from the front and compressing in the back a little bit more to prepare the vagina for birth. That’s pregnancy.

During birth, the uterus is contracting. The vagina is getting ready to open and the cervix is dilating so we can push the baby out.

The baby comes out vaginally (or by C-section sometimes, but usually it’s vaginally), and what happens there is that our pelvic floor has to lengthen two and half times its normal length in order for the baby to come out. And a lot of times, that’s where injuries can occur.

Let’s define the pelvic floor

Meg Collins:

I was always told as a visualization, as a lay person, that the pelvic floor is the bottom of the grocery bag that’s holding your groceries in, your groceries being… your innerds. Is that accurate?

Allison Romero:

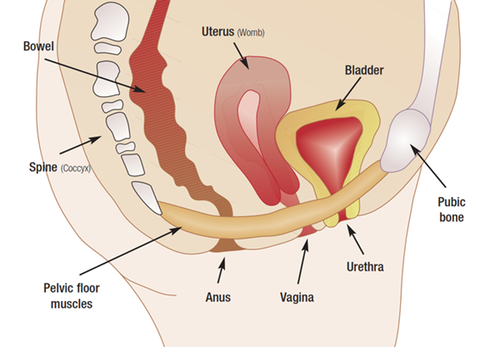

Yeah, the pelvic floor is a group of muscles that attaches from the pubic bone to the tailbone, essentially, and it looks like a hammock. It’s the bottom of our core.

The Core

The diaphragm is the top of the core, our abdominals are the front of the core, our back is the… back, and then our pelvic floor is the bottom.

It has three holes in it, for women (men have two, obviously). It has the urethra, the vagina, and the anus. So, it’s very important because it’s supporting our important organs: our intestines, our uterus, our bladder, that kind of stuff, but the holes are natural points of weakness. We need those holes, obviously: we need them to pee, [have sex], have babies, poop, etc.

During delivery, that pelvic floor, the perineum especially, which is the muscle that goes right between the vagina and the anus, is going to lengthen two and half times its normal length.

Two and a half times.

And that’s totally normal. Our body knows how to do that…. it does, but it doesn’t. There’s a first time for everything. So, often, especially with the first, we get some injuries.

We can get evulsions of the muscle, where the muscles can actually pull off of the bone. It happens in two-thirds of vaginal deliveries, and we don’t do anything about it because… we just don’t. Then, the other issue is, we can tear in the perineum. Usually… we do. If the tear is large enough, then it becomes a bigger issue down the line.

Meg Collins:

So, once you have babies and you talk about delivering babies with your friends, you actually hear about very few people who don’t tear – at least a little – during delivery, even if it’s a minor tear. So, that’s just kind of normal, right?

Allison Romero:

Totally normal. This is why we’ve shied away from episiotomies, though, or at least it’s not trendy to do them now, because what we’re thinking is… if you had a piece of fabric and you pulled, you might get a tear, but it would only tear so much and it would just tear in the natural weakness, whereas an episiotomy, they’re just cutting right through. So, it’s just easier to tear more.

Same with fabric. If you were to cut the fabric, it cuts right open and might be harder to stop.

Most people tear one or two levels, and when we grade it, we grade it through “levels of skin.” So, there’s the vaginal mucosa, which would be just a stage one tear. That’s such a little tear. Stage two would be into the muscle a little bit. Then, when we get into stage three and four, that’s going into the anal muscle and sphincter and mucosa to the rear, and that becomes a bigger problem.

Meg Collins:

Are we talking surgery for the higher level tears?

Allison Romero:

They’ll stitch you up and then we’ll see where we’re at down the road. OBs are really trying to avoid these tears, obviously. If people get a level three or four tear, they often need to present in front of a board at a hospital why that happened.

Meg Collins:

It’s not a good outcome.

Allison Romero:

It’s not a good outcome. It happens more often with forceps deliveries or vacuum-assisted deliveries, and it can cause major long-term incontinence down the road.

Meg Collins:

Are we talking, that’s pretty rare?

Allison Romero:

…on the rarer side. Not rare. Not as rare as we would like it to be, at least. Nobody wants that.

Meg Collins:

Yes. I know a friend who had a level 4 tear, and I think she’s permanently impaired. Not good.

Ok, switching gears: there is a term out there called “perfect pushing,” and I had asked you on one of my appointments, is that a thing? Is there a way that you can push your baby out that’s… better than other ways?

Allison Romero:

I don’t operate in a world where there is “perfect pushing,” but I think mother-led pushing, that’s not really the real term, but—

Meg Collins:

Versus the doctor telling you.

Allison Romero:

Yes, you tell yourself what to do. So, if you feel like you need to be squatting, that’s a good push for you. If you feel like you need to be on all fours, that’s good for you.

Meg Collins:

Your body knows how to position itself.

Allison Romero:

Yes, lying on your back with your knees up, like we see in the movies, is really not perfect for most people, and I think in some states, it’s more common that they really want you to be in that position, because that’s just the way it’s always been. Seems like in California, we’re getting more away from that. They’re giving birth bars and birthing stools and things like that.

Meg Collins:

But I will tell you, it’s still pretty traditional… at most hospitals [lying down, knees up] – especially with an epidural.

Allison Romero:

Yeah. I saw a woman from Alabama, and she said you must be lying on your back, pushing with your knees up. That’s just the way they do it. In a hospital, at least.

And that’s a problem. Like I said, birth is something that our body knows how to do. We’ve obviously been doing it since the beginning of mankind, but it’s not this black and white thing. So, pushing, I think, needs to be something that you intuitively find.

Meg Collins:

So you don’t have to study up on some technique, that’s good to know.

Allison Romero:

Yeah, and just one last thing about that is, I think sometimes we forget, or we don’t know how to push, and maybe that’s part of that technique. So, make sure that you know how to push; if there’s any question, that would be a good time to check with your OB or physical therapist, to make sure you know how to lengthen your pelvic floor. Sometimes people don’t know how to do that.

Meg Collins:

Okay. Or they’re afraid to. [in reference to pooping during delivery, etc.]

Allison Romero:

Or they’re afraid to.

Meg Collins:

So, let’s talk about the big problems that you see from your patients who come to you after they’ve had a baby. I came to her four years after I had given birth, which again, it was on my list of things to do… forever. I just… [didn’t have the time].

I was having problems with incontinence. I could no longer jog or jump or… do anything with impact, and so I came to Allison. I didn’t really know what she could do to help me, if anything. I think incontinence is probably the biggest [i.e. most common] postpartum problem, but what are the other problems that can happen during childbirth?

Allison Romero:

Yes, incontinence is a huge one. There’s urinary incontinence. There’s fecal incontinence, which comes into play usually with more of the level three or four tears. There’s organ prolapse. So, that’s when we get a softening of the ligaments that hold the bladder, the rectum, or the uterus.

Meg Collins:

And they don’t go back.

Allison Romero:

And they don’t go back.

Then, there’s pain. Pain is another big issue. Some people have pain with sex. Some people have just pain.

Meg Collins:

Or sex is different. [not in a good way]

Allison Romero:

Sex is different, yep.

Meg Collins:

Then there’s diastasis, which I also had.

Allison Romero:

Diastasis, yes [see separate video on diastasis].

Meg Collins:

Diastasis is an abdominal separation. I was under the initial impression that it was purely cosmetic, but in fact, it can be quite problematic.

Allison Romero:

Yes, like I was saying earlier, the pelvic floor’s a part of our core. The rectus abdominis is part of our core, too. The rectus abdominis is the muscle that looks like a six-pack. I’ve never seen mine myself, but I know it’s there somewhere, lol.

In 100% of pregnancies – in the third trimester, we get a diastasis. We’re meant to do that. Now, whether or not it goes back is the question; for some people it does, and for some people it doesn’t. If not, we’ve got two sides working separately and not communicating. And they’re a huge support of our bladder in the front. So, we need them there to be strong to keep things working. We need them to be working in conjunction. We need to be able to generate tension through those muscles.

Meg Collins:

And that’s something I still… can’t do.

Allison Romero:

We’re working on it.

Meg Collins:

We’re working on it, haha.

Allison Romero:

And it takes a while. It’s been four years. So, it takes time.

Meg Collins:

So, speaking of timing, when should a mom come see someone like you? What’s the ideal time someone should come see you? Let’s say… stuff has happened. Something’s not right. Your OB is not giving you any help — we’ll talk about traditional medical care and how it gets overlooked a lot, especially in this country.

Say the incontinence is not getting better or something just isn’t right. When would someone come see you?

Allison Romero:

The earliest, I would say, come at eight weeks. If things don’t feel right.

Remember:

It’s a big deal to have a baby. I consider it like a surgery. It’s a huge change to your body, and your body has to get over it. So, around eight weeks is when I feel comfortable assessing the pelvic floor. That’s the earliest to come in. If you are leaking then, come in. Let’s have a look. Let’s see what’s going on. Your muscles—I said they stretch two and half times their normal length. Did they stretch out so much and tighten up because that was a huge scare to them? Or did they stretch out and then stay that way and we need to strengthen them? The earlier we can fix it, the earlier it goes away, the earlier your body forgets about it.

Meg Collins:

Okay. So, definitely in the first year if possible.

Allison Romero:

Yeah. I would say in the first year, if possible.

Meg Collins:

Okay. That’s good know. Maybe for the next life, I can remember that, LOL.

Allison Romero:

Then, there’s life. You raise your child and do all that other stuff, but if you can fit it in, I would say, the sooner the better.

Meg Collins:

I had a six-week appointment, and then I had another appointment down the line with my OB, and I mentioned to him, I said, “Look, something just isn’t right. I’m having problems with bladder control when I sneeze, when I cough. I pretty much can’t do any sort of jogging or anything, really. Even bouncing hard down a hill.”

He says, “Oh, well, hmm.” It was sort of like, “Oh, that’s weird” sort of reaction. So, I really thought, “Gosh, maybe something is just wrong with me and this isn’t a thing and I’ll just have to live with this. This is just something bad that’s happened,” — wish I had a C-section!? I dunno.

I was just sort of just dismayed – but then when I started talking to people and they were like, “we’re going to go jogging,” and I was like, “Oh, I can’t because of…[notions to crotch area]” and they’re like, “Oh, well, you’ve got to go see a pelvic therapist,” and I’m like, “What? Who?” and everyone else chimed in, “Yeah, everyone does that and you’ve got to go,” and I was like, “What? Okay, okay.”

It was tribal knowledge, especially among runners.

So, it bumped up my priority list, and I finally went. I would have gone earlier if I had known, but I think that a lot of OBs in America don’t… know? Or they just don’t… address this with their patients postpartum — and that is a real shame, because if you talk to European women, they will almost always tell you, “Oh, no, I had to meet with someone in the hospital before I could be discharged. We had therapy afterwards, yada yada,” and it’s a regular course of events for them to do that. Here, it’s like a secretive thing. Do you have anything to say about that?

Allison Romero:

I totally wish it were more mainstream. Like I said, if you have a surgery, you get PT, and you work on your body, because things have been disrupted. With pregnancy, not only are you pregnant for nine months and that is, in and of itself, a big deal to your body, but then you have the baby. Whether it is vaginal or C-section, there’ve been major changes. So, I don’t want to speak on behalf of all gynecologists out there, because there are so many that refer patients to me.

Obviously, in the Bay Area, I feel like we’re getting there, but what I’ve gleaned from the gynecologists that I’ve spoken with is that… they learn the muscles in med school, then they go into their residency and they’re really not talking about that anymore. They’re talking more about cervical things or uterine things or vaginal things.

Procedural things.

They’re not talking about the muscles and their function as much, and I think they sometimes go by the wayside and they’re not talking or thinking about referring [patients] to physical therapy.

Meg Collins:

Right, and it seems that it is more so the rule than the exception (I’m very annoyed by this, as you can tell). Hopefully, that’s changing as time goes on and people become better educated about these things.

Well, I’m so glad to have found you. I am on the mend, I would say. I asked Allison in my appointment, “What’s the gold standard? Am I ever going to be able to… jump on a trampoline?” And she says…

Allison Romero:

You will.

Meg Collins:

Maybe.

Allison Romero:

You will.

Meg Collins:

Jumping on a trampoline, you guys. Can you imagine?

Allison Romero:

That is the gold standard for urinary incontinence.

Meg Collins:

I actually know very few moms who can do that without a little bit of leaking, and if you’re one of those moms who’s like, “I can do that,” you’re lucky!! Trust me. You’re lucky.

Let’s focus again on the incontinence here for a minute. Is there a percentage of women who are incontinent after having a baby?

Allison Romero:

Oh, my gosh, yes. It’s something like 38% of women are incontinent at any one time. So, if we just took a snapshot, it would be thirty-eight percent of American women.

Meg Collins:

And of course, it gets worse as you get older if it’s not treated.

Allison Romero:

Exactly.

Meg Collins:

Everyone knows their family members who use Poise, and such, as they get older. It’s definitely a thing with older folks.

Allison Romero:

It is, and that’s one of the biggest reasons people end up going into assisted living. And it’s something that is fixable, and we want to fix it early.

Meg Collins:

So, there are these generations of women who never got help, it’s kind of sad, because it needn’t be that way. I’m sure obesity only adds to it, and just… other lifestyle problems that tend to develop as we age.

Allison Romero:

Yeah, I don’t have a hard and fast percentage of postpartum women that are dealing with incontinence, but it is a lot of women at any given time. Thirty-eight percent is a lot of people, period. So yes, very common; and for some people, it goes away – and for some people, it doesn’t. So if it’s there and it’s been a couple months after you’ve had the baby, it’s worth checking in with a therapist.

Meg Collins:

And I asked you at my appointment, is it because I’m older? I was in my mid-30’s when I had my two babies and…

Allison Romero:

It’s totally not, no. Age doesn’t really have anything to do with it. They’re finding that genetics is the number one predictor. So, if you have a mom, sisters, etc., that have dealt with incontinence, it will probably happen to you. It also has to do with our “ligamentous laxity.” So, that means how mobile we are, how flexible we are.

Women tend to be more flexible anyway because we have babies. We need to be able to stretch, but then, people that tend to be extra flexible are the people that tend to have more problems.

Meg Collins:

Switching gears, I know that there may be some hang-ups, maybe, about the intimacy of what’s going on at these sessions, and what I would say about that is… it’s no worse than going to your OB for a pelvic exam.

Allison Romero:

Agreed, the typical first time appointment would be, you come in, we talk for maybe 15 minutes about what’s going on, and then I would have you undress from the waist down and then you’re covered, but we’re just undressing from the waist down so that we can look at the abdomen and we can look at the muscles that attach to the pelvic floor externally, and then we can look at the pelvic floor internally.

Usually that’s vaginally. If someone has anal issues, we will check rectally, but usually we check vaginally and that way, we can also check the bladder. We can check the rectum. We can look at the urethra. We can assess [general] strength, the perineum, everything.

That exam is with one finger in the vagina, being able to palpate the muscles that way.

Meg Collins:

And from that, you can figure out what’s going on — in general. Then, from there, you prescribe exercises. It’s therapy just like anything else, right?

Allison Romero:

Just like anything else.

For some people, their issue is that their muscles are too tight, and that can lead to incontinence, because you can imagine if your muscles are too tight and they need to squeeze to hold pee in, they can’t because they’re already as tight as they’re going to get. In that case, we need to loosen them, and then re-strengthen them.

For some people, the pelvic floor muscles are sluggish. I don’t want to call them loose, but just weak. Then, we just need to strengthen them. You can tell that right away.

Meg Collins:

During my first exam, we did some Kegels, and I think I said something like, “I can’t really feel…those muscles anymore” — because I remember doing Kegels before having a baby, and then trying to do Kegels now, especially after so many years have gone by, it’s like flexing a muscle that I can’t really feel, and then we discussed the desensitization.

Allison Romero:

Yeah, so what they found in the research is, after we have a baby and the muscles lengthen, it’s a big deal to the body, and the brain is like, “Whoa, okay. That was a huge ordeal,” and you have a newborn baby now — it’s important stuff, and you have to care for the child – there’s a lot going on.

So, the brain’s like, “This [issue] is not life-threatening. So, what I’m going to do is, I’m going to actually take some of my nerve input away.” I always think of it as – remember in the Wizard of Oz, when the house falls on the Wicked Witch of the East in the beginning, do you remember that, and the feet roll under? That’s kinda what the nerves do, here. They’re trapped. So, the brain’s like, “Yeah, I’ve got to do all sorts of stuff. This is not life-threatening.”

Meg Collins:

The brain shuts it down a bit?

Allison Romero:

It just does the bare minimum. It gives the bare minimum around the nerves to function, sort of. And what they found in research is that it doesn’t just… come back on its own. You have to physically re-learn it and re-grow those nerves to do what we need them to do (i.e. hold pee in), and that takes a lot of thought and retraining. It takes a lot of habit changing. It takes strengthening.

Meg Collins:

I know that a lot of people know what Kegels are. Kegels are when you tighten your — you can probably explain it better…

Allison Romero:

Kegels are just a contraction of the pelvic floor muscles. So, you’re squeezing up and in.

Meg Collins:

Pre-kid, I was used to doing them in traffic or doing them on the subway just to get them done, and that’s not really ideal, right?

Allison Romero:

Right, it’s not that people are particularly weak; it’s just that our neuromuscular connection is not there anymore. So, it’s not a great idea to be in a frenzy doing them, like, “Oh, I’m at a stoplight. Let me get five in here.” I actually want you to set separate time apart where it’s quiet.

Meg Collins:

And it’s harder than you think.

Allison Romero:

No kids, no husbands. You need seven minutes of alone time to concentrate.

Meg Collins:

Also, I find it’s also easier to do on a hard surface.

Allison Romero:

A hard surface gives you a little bit more feedback. Everyone’s different: for some people, it works when they’re standing, for some it’s sitting, and for some people it works better when they’re lying down.

Meg Collins:

But you have to be concentrating. You cannot be checking Facebook or watching TV.

Allison Romero:

It’s really important, because you’re growing nerves. That’s really what you’re doing.

Meg Collins:

And the other thing you told me was – when I’m sneezing or coughing – to really focus on that squeeze instead of – crossing my legs real quick like – and concentrating on it has been working for me [to not leak while sneezing], which is awesome! So, I do feel like I am sort of learning how to let my body and my brain do its job. It’s old job, at least.

Allison Romero:

Yes, and it’s totally easier said than done. We call it the “knack,” though, this is a habit that your brain had before you had kids. You would just sneeze and your body would catch it. You wouldn’t need to cross your legs.

Now, it’s like, “Whoa.” The sneezing catches your brain off-guard. It’s asleep at the wheel. So, you’re reminding it. “I know a sneeze is coming, so I’m going to squeeeeze…” – and then sneeze.

You can’t do it on the trampoline. So, sneezing and coughing works because we kind of know that’s coming. That’s when I want you to catch it. But jogging, trampoline, etc., your brain has to “be there” for you for that. That’s why it’s the gold standard.

Meg Collins:

Okay so, the Kegels themselves, you gave me very specific exercises to do, and I think most people, when they do Kegels, they are just squeezing, releasing, squeezing, releasing; but there’s more to it than that.

Allison Romero:

Yes, a Kegel, like I said, is squeezing the pelvic floor. It is your pelvic floor muscle contraction.

Meg Collins:

And by the way, you want to squeeze…. [we’re going to talk about it all, y’all, so don’t get shy.] In a Kegel, you should be squeezing both where you would stop your pee, and your butt area.

Allison Romero:

Butthole.

Meg Collins:

Butthole! Yes.

Allison Romero:

Yeah.

Meg Collins:

So, it’s that whole deal —it’s like a figure eight, right?

Allison Romero:

It is. It’s a figure eight that goes from your urethra, your pee hole, around the vaginal opening, around the butthole, and back up again.

Meg Collins:

So, it is really a larger area than just the front. Wanted to share that in case people didn’t know.

Allison Romero:

When I’m doing a Kegel, I imagine the pubic bone and tailbone squeezing together.

Meg Collins:

Pubic bone to tailbone. Okay, yeah. I like that.

Allison Romero:

Right. So, you’re getting it all, and you’re pulling up and in. Up and in.

Meg Collins:

So, the exercises you gave me are a little bit more in-depth than just a regular Kegel.

The various PT Kegels for pelvic floor conditioning

Allison Romero:

Yes, a regular Kegel would be just the strengthening portion of your workout. It’s just squeeze, relax; squeeze, relax. You’re not holding for any specific amount of time. You’re just squeezing and relaxing, and usually I would do 30 of those.

And that’s akin to doing your bicep curls. There’s been research out there that shows that 30 Kegels is kind of enough to maintain good bladder control.

Meg Collins:

To maintain. So, once you do get to the place where you want to be, eventually, 30 Kegels (per day!) is enough for most people.

So guys, this is a lifetime thing. This is not a once and done thing. I’m better.

You have to keep at it.

Allison Romero:

You do!

Meg Collins:

And it’s worth it, right? To not be that person in the nursing home who’s incontinent.

Allison Romero:

I totally agree.

Meg Collins:

I want to be that guy who can, like, run after their kids suddenly; like when they take off running into the street and you pee yourself and you’re like, “Ahh, great.” I don’t want to wet myself.

Allison Romero:

It makes your day a little easier if you don’t.

Yes, so we’ve got regular Kegels, which are like a bicep curl. We have the “holds,” which would be for endurance. It’s akin to the a long-distance run.

Meg Collins:

So, that’s squeezing a Kegel and holding it. “Holds.”

Allison Romero:

Squeezing and holding.

Meg Collins:

Which is really hard. With the Holds, I started at eight seconds (my max duration when I started), and now I’m up to 16 seconds, and the ultimate goal would be…

Allison Romero:

One minute.

Meg Collins:

A whole minute, dang! I can’t ever imagine… ever being able to do that. But I’ll get there, hopefully, lol.

Allison Romero:

And 30 seconds is a really good mid-point goal. So, you started at eight seconds and I told you it’s a one second improvement every one to two weeks – that’s as good as we can ever expect.

Meg Collins:

So, we’re talking a half a year to a year to get there. Dang!

Allison Romero:

Exactly.

Meg Collins:

So, this is work, gang! This is work, just like any other therapy that you would do.

Ok, the next kind of Kegel we did was the “elevators.”

Allison Romero:

Yes, the elevators, which are really our dexterity and control over these muscles. With the elevators, we break it into three parts. So, you’re trying to squeeze a little bit (level 1), a little bit more (level 2), all the way to your max squeeze (level 3); then let it go down in 3 stages same way.

Meg Collins:

Those definitely require the most concentration, in my opinion. Although the holds are quite hard too.

Allison Romero:

You can feel your brain on that one. Those are the elevators, and they’re really just there for you to be in total control of those muscles.

Meg Collins:

And then the fourth kind of Kegel is the “quick flicks.”

Allison Romero:

Quick flicks, yes. The quick flicks are more about power and speed. They are there for you when you sneeze, cough, jump. Sudden things like that.

Meg Collins:

So you can react quickly.

Allison Romero:

Exactly. So, they’re a Kegel, but you’re trying to squeeze it as fast as you can, kind of snap it back and let go.

Meg Collins:

It’s fast like “chh-chh-chh-chh.” [watch the video, this is hard to describe with words]

Allison Romero:

Exactly. So, I usually have you do them in sets of five. One, two, three, four, five, relax, and start over. One, two, three, four, five.

Meg Collins:

Ok, That was good because I don’t think people know that there are all these different types of conditioning that you can do for your pelvic floor.

Finding a PT

Switching gears now, how does someone go about finding someone like you? What are you called? Where are you found? All of that.

Allison Romero:

So, I am a physical therapist, and I specialize in the pelvic floor. So you’re looking for a “pelvic floor physical therapist.” It’s not often in their name or credentials. Often, it’s in the company’s name, something like that. We are the Pelvic Health and Rehab Center.

The two best ways to find a pelvic floor specialist right now is to go on the American Physical Therapy Association Women’s Health page.

You can also look in the International Pelvic Pain Society – you can look it up by State.

Meg Collins:

Obviously, it’s going to be easier if you live in a metropolitan area versus living out in the country somewhere, but I think one way or another, people will be able to find somebody who’s somewhat close.

Allison Romero:

I think so. This therapy is getting to be more mainstream.

Meg Collins:

And the number of visits someone should expect; a handful, maybe?

Allison Romero:

Yes, it depends; it takes a minimum of 8 to 12 weeks of therapy to really see a meaningful difference in your life. So, the first four to six weeks of doing physical therapy doesn’t mean you’re going to be in the physical therapist’s office every week. I mean, the first four to six weeks is just your brain growing nerves, and then in 8 to 12 weeks, your muscles are actually starting to take it on and get stronger.

And then, you have to keep doing it. You started at eight seconds; we want to get to sixty. It’s going to take a good year, year and a half, that kind of a thing.

Meg Collins:

There’s a lot of damage that has to be undone here.

Allison Romero:

Yeah and a lot of times, I’ll have to start maybe once a week for the first one or two weeks just to make sure we’ve got the whole program down, and then we’ll go to once every two weeks for a couple visits to make sure we’re still on track. Then, I may say, “Okay, go for a month, do your thing. Let’s check back in and see, just make sure, we’ll up the program as necessary.”

Meg Collins:

Then, do you see people once a year? Do you have an ongoing maintenance appointment or anything?

Allison Romero:

We do, yes. Some people feel like, “I’m good.” Some people feel like they just want to check in and make sure it’s all-good once a quarter, once every six months, whatever.

Meg Collins:

Or they maybe backpedal a little bit.

Allison Romero:

Of course. Sometimes you just get cavalier, so you’ll want to come in again to recover some lost ground.

Meg Collins:

Insurance. Does insurance cover this, typically?

Allison Romero:

So, here’s the problem with insurance. Insurance covers physical therapy, and we are billing physical therapy codes. The problem with pelvic floor physical therapy is that the business model has to be different. We have to be one-on-one, in a closed-door room. Nobody helps.

So most practices have gotten away from billing insurance because they are not getting reimbursed enough to make their practice work. So with most of these companies, we gave you a super bill, you give it to your insurance, and it’s billed as an out of network service.

Meg Collins:

And by the way, it’s still well, well worth the money, in my opinion, to get this stuff fixed, because think about all the stupid things you spend money on in your life. To fix your own body and to take care of mom is super important. I’m really bad at it.

I’ll go to the mall to buy myself something and I’ll buy my kids some shoes and come home with nothing for myself, for example. And I think it’s just so important for us to remember to take care of ourselves, and this is such an important thing for us to take care of.

Ok great, is there anything else, any other big points that we want to hit in this segment?

Allison Romero:

I think we did pretty good.

Meg Collins:

All right, awesome! Thank you guys so much for watching. Please take care of your pelvic floor. You’ll be so glad you did. And your husband (maybe?) will be happier, haha. We’ll see. Signing off. See you next time. Thanks a lot, Allison.

END OF RECORDING

Thank you so much! I’m just started pelvic floor therapy six years after giving birth. I thought incontinence while sneezing, coughing, and laughing was just something I had to live with.